By Leader Contributor Alexandra Jo, Culture and Content Manager at Parting Stone

Sacred grief practitioner and deathcare educator Joél Simone Anthony firmly believes that death, dying, grief, and mourning are sacred spaces.

As deathcare professionals, our job is to help people experiencing personal loss understand what is happening and move through grief with intention and support. Our jobs are meaningful and important, but they can also come with large amounts of heaviness. Compassion fatigue and emotional burdens can be difficult to deal with once the workday is done.

The heavy nature of our work, coupled with the fact that many funeral professionals aren’t making huge salaries, can cause stress and tension for many deathcare workers. Knowing that our work is valuable and important can feel in conflict with the discomfort that comes with asking to be paid for it. For these reasons, we often see funeral directors burn out and leave deathcare only a few years into a career. And, our profession isn’t seeing huge increases in workers year-over-year, even though total death rates in the U.S. have been consistently on the rise over the past decade and our facilities have been at max capacity throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, it stands to reason that learning how to take care of our own emotional and financial needs as professionals in the deathcare space can have lasting effects on our careers and the families that we serve.

Total Deaths Rising, Funeral Workers Disappearing

According to a survey for funeral professionals put out by Connecting Directors earlier this year, “recruiting and retaining quality employees” was identified as the biggest challenge among deathcare workers. Since employee retention is such a problem, this begs the question: Why are funeral directors leaving the profession when it feels like they are needed most?

Even before the pandemic, total death counts in the United States have been increasing year-over-year as life expectancy has alarmingly fallen among middle-aged and younger Americans in the last decade. While this means more imminent business for funeral homes, it also means more strain on the professionals who work in deathcare.

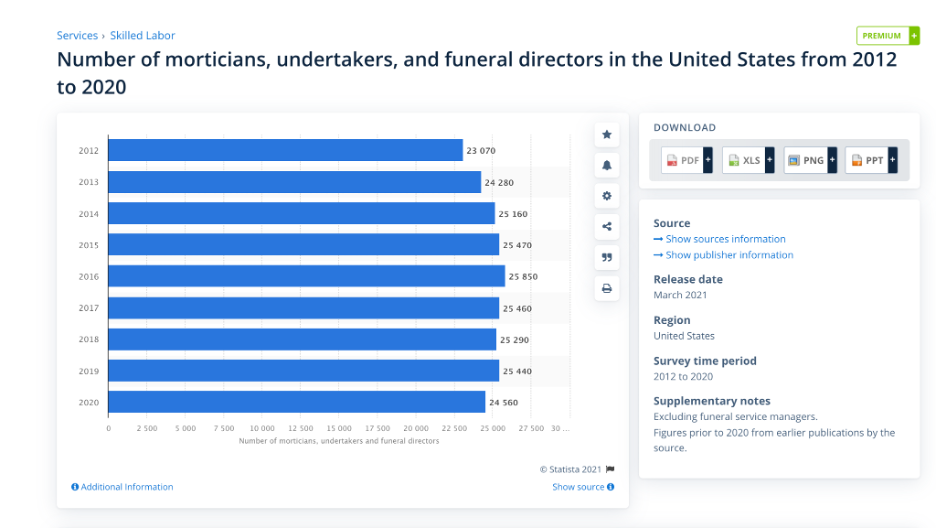

In the past decade, the total number of funeral directors in the U.S. has not increased along with rising death counts in the U.S. According to DataUSA.com, deathcare has only seen an average increase in workers of 6% in the past decade, and the website projects a -1.8% decrease in total deathcare workers in the US over the next year. Data from Statista.com concurs that the total number of funeral directors in the U.S. fell in 2020 compared to 2019.

Furthermore, according to NFDA statistics, the total number of funeral homes in the U.S. has been gradually falling year-over-year since 2009. This negative growth projection is distressing, as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Delta variant have continued to cause extreme amounts of excess deaths across the U.S. throughout 2021.

As numbers of funeral professionals decline, work stressors are compounded for the funeral workers who are in this profession for the long haul. Compassion fatigue and burnout are real issues for deathcare professionals. The emotional burden of deathcare, coupled with the long hours and low pay, leaves many deathcare workers strapped for the time and resources needed to meet their own needs in order to avoid burnout and lead healthy lives.

One former funeral professional described their choice to leave deathcare in an interview with the DeathTalks blog, “I was reaching my 30s and realized that I wasn’t making a lot of money. I was constantly broke living in the city with car payments, rent, bills, and a social life, and the scheduling of work was making it difficult to get a second job. I wanted to move up, but the people above me weren’t going anywhere, and I felt really stuck.”

What We Can Do Better: Identifying Our Needs as Deathcare Workers

On a recent episode of the Deathcare Decoded podcast, Joél Simone Anthony discussed some of the needs that deathcare professionals have, including financial stability and emotional support, and how we can practice self-care by learning to be aware of them in order to ask for what we need from our families, our jobs, and ourselves. Understanding that funeral professionals need mental health support and financial security, and then working to make those needs met for our employees can help with the employee retention problem faced by our profession as a whole.

Emotional Support

Arguably more than many other professions, deathcare workers need reliable, consistent emotional support. Another high-ranking problem on the Connecting Directors survey was mental health and compassion fatigue, with 32.31% of deathcare professionals citing mental health as a professional challenge, making it the second-highest ranked hurdle faced by funeral homes today.

Whether mental health support comes from a group of trustworthy peers or from a professional counselor who specializes in death work, having a healthy outlet for intense emotions and the weight of our work is important. Jody Herrington elaborates on the importance of normalizing mental health support in the deathcare space in this interview with the Deathcare Decoded podcast:

Click the button below to download a free ebook of mental health resources for funeral professionals that you can share with your employees or co-workers:

Funeral professionals also deserve to be paid fairly for the services they provide. This can be difficult, especially for independent businesses on shoestring budgets. However, working to change society’s larger perspective of deathcare can help instill perceived value in the services that funeral professionals provide to the public.

Financial Support

Our services have intrinsic value for the individuals that we serve directly and for society as a whole. There should not be shame associated with being paid for our labor.

Joél Simone Anthony elaborates on the Deathcare Decoded podcast:

“It’s not that there is a problem with [funeral professionals] raising our prices, it’s that we haven’t been charging enough all along. There is value in what we do as deathcare professionals. There is value in knowing how to care for a deceased human being; reproducing facial features, hair and makeup, embalming, planning, and being able to communicate with and get information in order to file necessary legal documents. There is value in that. When I consult with my own lawyer, I can’t think of one of my contracts that cost less than $750 to draft, and that’s one document […] How many contracts do you sign at the time of death? How many official government documents do you have to fill out at the time of death, then get back within 48 hours? People have become so accustomed to paying $5,000 or $6,000 total for us to do all of these things around death because that’s what we have always accepted for our work. Why? I’m not saying you have to charge someone $10,000 for one thing … you can’t overcharge someone, but you also can’t short-sell yourself. So, my theory is to come out of the gate knowing your value, and they don’t teach us that in mortuary school. We are taught that if you make $40,000 per year you’re doing great, and honestly, that is insane.”

Self-Care in the Deathcare Space

There are many resources available for deathcare professionals when it comes to mental health and emotional support. Joél Simone Anthony offers a self-study course called Self Care for Deathcare Professionals. You can also click the button below to download a free Mental Health Resource for Deathcare Professionals to share with your employees or colleagues.

When it comes to employee compensation, funeral homes can take steps toward fairly compensating their employees by considering things like local true cost of living (NOT local minimum wage!) and the value of services provided by employees. Help employees see a clear path of upward mobility, including promotions, scheduled raises, and increasing levels of responsibility. Being open to conversations about pay and benefits is also an excellent place to start.

It’s true that not everyone is cut out for the deathcare profession, and a certain percentage of new deathcare workers might decide to change careers eventually but taking stock of how employees can be supported and support themselves better will have a positive impact on retaining workers in this professional space.

Encouraging self-care regimens for your staff will also have positive effects on the wellbeing of employees who are in this profession for the long haul. Our job is taking care of others in one of the most difficult times they will experience. The bottom line is, in order to do that well, we’ve also got to take care of ourselves.