Excerpt Published with Permission from the Cremation Association of North America / The Cremationist V57 i1, © 2021

Bereavement professionals such as funeral directors, embalmers, cemetery workers, crematorium operators, and their support staff may regularly engage with diverse, potentially psychologically traumatic events.

These exposures can lead to a variety of mental health injuries, including post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, and alcohol use disorder. Recent research has provided important information about those experiences, such as the scope of the challenges, the potential impacts on mental health, factors impacting health, and some of the opportunities to help protect mental health and provide support.

Dr. R. Nicholas Carleton, a professor of psychology at the University of Regina and a registered clinical psychologist in the province of Saskatchewan, introduced his discussion on challenges, strategies, and coping by emphasizing that it was really an introduction to mental health.

“I’m currently serving as the scientific director for the Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment, which is part of where we’re going to draw a lot of the research data that we have here today,” Dr. Carleton said, by way of disclosure. “I have no conflicts of interest and certainly no commercial interests. My research is supported by a variety of different federal and provincial agencies.”

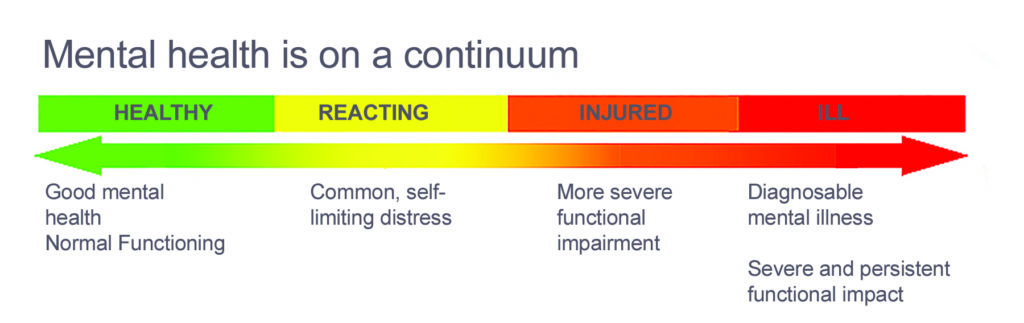

He began with a high-level conversation about mental health, pointing out that it is “super-critical for all framing” to understand that mental health exists on a continuum (see Figure 1, below).

“There’s a long-standing notion that we are either mentally healthy or mentally unhealthy and none of the data bears that out,” Dr. Carleton explained. “It’s simply not the case. Most of us, throughout the course of a day—and certainly throughout the courses of weeks or months on end—we shift along a continuum from healthy, to having reactions, to possibly being injured, to being ill or meeting diagnostic criteria for one or more mental health disorders. And this is normal.”

Odds are that people probably experience changes in their mental health throughout the entire day. Dr. Carleton described a scenario where someone wakes up in the morning and everything is fine and that’s terrific, only to move on and have somebody cut them off in traffic, and for a few minutes, they might be reacting—might even be “injured” for a few moments—but they recover very quickly and then they’re at work and moving on with their day.

So we shift throughout the entire day and all of this happens in an environmental backdrop that we often forget is having the impact that it is.

Right now, all of us are sharing a massive significant environmental variable that’s impacting our mental health—and that’s COVID-19. The impact of the pandemic is underlying all of the other things that impact us, including our biology. If we’re sick, if we have a flu, if we have a cold, that impacts our mental health. If we’re healthy and we’re exercising regularly, we’re active, that impacts our mental health and our mental health impacts our physical health as well.

If we’re not feeling very happy about something, if we’re worried, if we’re depressed or down, that has a reflection in our physical capacities. We also see those same kinds of challenges with respect to our social environment. If everything is going well with our friends and our family and we’re regularly engaged, that also serves a protective function so that we’re more likely to feel physically healthy and we’re also more likely to feel psychologically healthy. Our biology, our psychology, and our social environment all come together on an overlapping Venn diagram that sits on top of our environmental stressors.

It’s important to remember that there’s not one thing that causes any specific set of things to occur for our mental health. It’s always a combination.

Dr. Carleton informed listeners that it’s also important to remember that it has nothing to do with inherent weakness. “We have no evidence that says that there’s one gene or one feeling or one thought or one behavior or one experience that is solely responsible for our mental health or mental state. And certainly not for having difficulties with mental health,” he said. “When we talk about people who are having difficulties with mental health in most cases it’s a function of high stress or chronic strain or physical exhaustion and maladaptive coping all coming together to challenge an individual’s experience.”

He pointed out that anyone can develop symptoms, saying, “You can have a tremendous amount of expertise with mental health, you can know how to treat mental health injury, and you can still end up with a mental health injury. At the end of the day, even the most resilient of us is still human. We still experience all kinds of highs and lows in our lives.”

Dr. Carleton underscored that only licensed qualified experienced persons can and should diagnose disorders or imply diagnosis. “Dr. Google gets us part of the way there in some cases, but that’s not super reliable,” he said. “If you’re looking for help with mental health or you’re concerned about your mental health, you want to talk to a registered, licensed, evidence-based mental health care provider who can provide you with information about where you’re at and possible solutions to get you to where you’d like to be.”

Moving on to talk about potentially psychologically traumatic events that might apply specifically to some of the the work that deathcare professionals perform, Dr. Carleton spoke of experiencing, witnessing, or learning about something potentially injurious to a close relative or a friend that may cause mental health injury. He said that other potential events include repeated exposures to distressing details of significant threats such as exposure to war, threatened or actual physical assault or sexual violence, kidnapping, hostage-taking, torture, and mechanisms of severe physical injuries, like motor vehicle accidents and industrial accidents.

“You’re exposed to these things because if someone dies as the function of one of these events, the last responder is you and so you are exposed to these on a regular basis,” he said. “As a species humans are generally resilient and adaptable. So even these kinds of events, when we’re exposed to them, we can bounce back, we can recover. Most stressors—even repeated exposures to these kinds of events—are not typically overwhelming. But you have to remember that our experience of whether something is overwhelming is influenced by our biology, our psychology, and our social environment, as well as what’s happening behind the scenes in our broader environmental variables.”

Dr. Carleton was talking specifically about events that are potentially psychologically traumatic. He said that the most common thing we think of is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) when we think about a mental health injury. PTSD can be one thing that happens following exposure to one or more potentially psychologically traumatic events where we don’t bounce back, where we aren’t able to be as resilient in that moment because of any number of things that have come together.

Broadly speaking, the symptoms for PTSD may include intrusion symptoms, such as dreams or flashbacks; avoidance symptoms, like not wanting to think about or talk about the event; negative mood with dissociative numbing symptoms like depression, detachment, or the inability to feel happiness and changes in your reactivity; and hyper arousal symptoms, like trouble sleeping, irritability, self-destructive behavior, and hyper-vigilance.

All of these are symptom clusters that—if they’re experienced for four or more weeks and cause interference more days than not for most of the day—may meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s a mental health injury for which there are effective treatments that can provide symptom relief for a great many people and it’s one of the disorders that can follow exposure to the kinds of traumatic events Dr. Carleton listed. It’s also not the only mental health injury or disorder.

Major depressive disorder is actually more common, even among people exposed to these ongoing potentially psychologically traumatic events. Symptoms include depressed mood or diminished interest in activities; significant weight loss or gain, appetite change; insomnia or hypersomnia; observable psychomotor agitation or retardation; fatigue, loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt; diminished concentration, indecisiveness; thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, plan, and/or attempt.

If you experience five or more of these symptoms for two or more weeks, most of the day, nearly every day, you might well meet criteria for major depressive disorder.

“There are also difficulties with substance abuse and dependence disorder,” Dr. Carleton explained. “You’re taking the substance for longer than you expected. You’re taking the substance in order to avoid or manage symptoms that you’re having or to change your emotional status. In a classic quote from one of my colleagues, she said, ‘You know, the problem isn’t necessarily volume. It can be the amount that someone’s consuming. But more often than not, the challenge can be that one drink might be too many and ten might not necessarily mean there’s a problem.’ It depends on how you’re using and what you’re using for. And if you’re using as a function of trying to manage other symptoms, that’s a good indicator that you can probably benefit from some additional support. It’s not the only indicator, but it’s certainly one of them.”

There’s a host of such mental health injuries that are associated with different diagnostic categories, all of which may warrant attention and all of which can benefit from additional interventions from a professional mental health provider.

Dr. Carleton turned to discussing some of the urgent warning signs and symptoms. First, he pointed out that if any of the symptoms that he covered previously lasts longer than a week, at that point it’s a warning sign that your symptoms may benefit from some intervention, particularly difficulties with falling or staying asleep, intrusions, numbing, changes in your behavior, or sudden increases in substance use. Those are also potentially urgent warning signs and symptoms.

Suicidality, homicidality, violence, or sudden dramatic increases in substance use should all be taken as urgent warning signs where it’s time to get in to see somebody soon. “It doesn’t mean necessarily that we need to call 911, although that is a possibility,” Dr. Carleton said. “It does mean that help is needed sooner rather than later.”

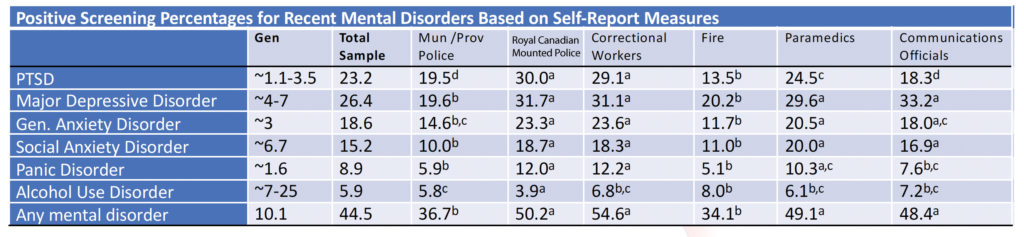

Dr. Carleton and his colleagues looked at public safety personnel, including police, firefighters, paramedics, correctional workers, and communications officials—people who are regularly exposed to potentially psychologically traumatic events. They compared their responses on measures of each of the major mental health injuries to the general population (see Figure 2, below).

“For PTSD, for example, for the general population it’s around one to three-and-a-half percent, depending on who you ask at any given time who meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder,” the doctor pointed out. “But if you look at our sample of people that are regularly exposed to potentially psychologically traumatic events, we’re looking at 23%, with some variability across the board depending on which profession you’re looking at. We saw similar patterns for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and even alcohol use disorder in some cases.” These groups are reporting much higher levels of symptoms and much more difficulty with major mental health disorders than the general population.

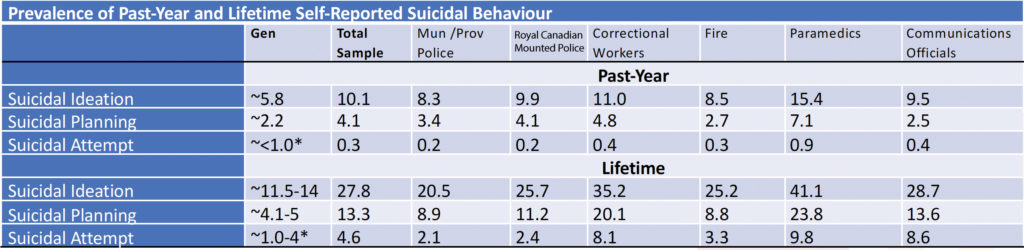

There was a similar pattern found for suicide—particularly suicidal behaviors, like ideation, planning, and attempts (see Figure 3, below). Dr. Carleton encouraged people to be very careful because those same groups that are regularly exposed to potentially traumatic events were reporting much higher levels—almost twice this high and sometimes even more than that—as the general population. He said that ideation, planning, and attempts should all be taken very seriously because they’re the best predictors that we have that someone may die by suicide.

“What can you do? Well, I think first and foremost it’s important to keep in mind that mental health is a journey, not a destination,” Dr. Carleton advised. “It’s not something you check off as a tick box because you did it well today, any more than physical health is.”

He encourages deathcare professionals to monitor both their physical and their mental health. “We have tools that we make publicly and freely and anonymously available on our website for our public safety personnel, and those tools might be beneficial for you as well,” he offered. “They allow you to compare your responses to the general population, and, in doing so, you get immediate anonymous feedback that you can use to see where you are sitting relative to everybody else.”

Because changing mental health requires culture change because of stigma and misinformation, it’s extremely difficult and takes a long time to accomplish. Dr. Carleton believes it’s important that we all pay attention to the idea that mental health is something we’re trying to change at a population level, but he pointed out that for people who are regularly exposed to potentially psychologically traumatic events, they may very well be forced to engage with culture change more directly than everybody else. He encouraged listeners to engage in ongoing monitoring regularly and get help sooner rather than later.

He directed everyone to apps that are available for other populations regularly exposed to stressors, such as The Road to Mental Readiness. That’s just one example of an app that’s freely available from the Canadian Department of National Defense.

What can we do in addition to the monitoring? The doctor advised people to look to their social support. He said the best data suggests that significant others and spouses can be particularly helpful, as long as the relationship is positive and “there’s lots of open communication. Otherwise, it is possible that those social relationships can be particularly problematic,” Dr. Carleton said. “In either case, if you’re not sure, get additional help and resource access. Talk about your experiences. Not necessarily about the details of what happened in your job and specific day, but how you’re feeling and what else you’re doing in order to manage those feelings. If you’re having difficulties with the symptoms we’ve discussed, talk to family or friends. Make sure that you keep a regular diary so that you can watch what changes for you that supports or undermines your mental health.”

“As cliche as this sounds—and it sounds cliche in part because we all keep saying it—engaging in regular healthy behaviors enhances your coping ability and helps to maintain your mental health,” he continued. “So, exercising regularly, believe it or not. For those of you that are of my generation and remember a certain fellow jumping on a couch on TV, screaming that exercise was to cure to all mental health ills, that’s not true either. But exercise, even light exercise: simple walks, getting outdoors, 20 minutes. Any exercise at all tends to be beneficial as long as it’s regular.”

Dr. Carleton added that people should watch what they eat. Eating healthy is important because the highs and lows of sugar affect your biology, which impacts your mental health as well. Substance use and misuse is much more problematic and a much more slippery slope than most people realize. If, for example, you’re using alcohol to manage your emotions, that’s a good indication that there’s a better set of skills you can access to manage those emotions.

He also emphasized that, where possible, it was important to maintain routines, even in the face of COVID-19. “The more routines that you can build in, probably the better off you’re going to be, as long as those routines include strict work-life balance where possible,” Dr. Carleton said. “As a professor, I can tell you that the boundaries between my work and my life are permeable at times. They’re permeable most of the time, but it’s important to try and manage those separations because that’s what’s helping to protect and sustain your mental health. So making sure that you’re managing that is an important part of living an ongoing happy, healthy career.”

Last but not least, Dr. Carleton addressed early evidence-based interventions. “You want to be very careful here,” he cautioned. “Evidence-based interventions are evidence-based for a reason. It’s because they’re helpful. It’s because they’re beneficial and there’s proof, there’s research that says that they work.”

He spoke of the importance of finding the right type of practitioner to offer those interventions. “Psychologists is a protected term. So is psychiatrist. But counselor, therapist, and healer are not protected,” he warned. “You want to be a counselor or a therapist today? Congratulations. You’re a counselor, therapist, or a healer, because you decided that’s what you wanted to be today. They’re not legally protected terms, which means that anyone can take them—and there is a lot of variability among them. That doesn’t mean there’s not good counselors, therapists, and healers. It’s just that there are a lot fewer restrictions on those names and titles than there are on things like psychologist or psychiatrist. So I recommend you demand registered and licensed, experienced, evidence-based, empirically-supported mental health care (which is a mouthful!), but you can find that from colleges, registered provincial associations, and registered state associations.”

Dr. Carleton pointed to a host of programs that are claiming they can increase resilience and resistance and protect people. “I can tell you from recent research that we’ve done that there’s still insufficient evidence that any of these work the way that they are saying that they work and there’s no way to determine that program A is better than program B. We don’t see evidence that they are harmful, but we don’t see evidence that they are necessarily more or less helpful than any other program that you would compare them to for protecting mental health, so, please be careful,” he warned.

Just about anything you do to protect and work on your mental health seems to help at least a little bit, according to Dr. Carleton. “For people who are exposed to potentially psychologically traumatic events on a regular basis, the best way to prevent injury to their mental health would be to not be exposed in the first place. That’s not necessarily practical, which means we’re really talking about secondary or tertiary prevention, which means early detection and improved quality of life if you are having challenges. So those are the places I tend to focus,” Dr. Carleton summarized. “Catch it early, work to make sure you’re balancing it, and if you’re in trouble, get help soon so that you can get back to healthy as quickly as possible.”

There are several additional resources that have been made available on the Canadian Institute for Public Safety and Treatment website (www.cipsrt-icrtsp.ca). Dr. Carleton encouraged everyone to check the information there. He said the glossary is particularly useful because there’s a lot of misused terms out there and his group has tried to clean that up in a user-friendly fashion with specialist’s and generalist’s information available for everyone. He also recommended viewing the PTSD 40th anniversary video. “If you’ve enjoyed listening to me or if you found that I’ve helped you to be more sleepy, you can listen to me speak about the great history we have with PTSD. We’ve come a long way in the last 40 years, but we’re looking at a hundred years of history of trying to manage these challenges,” he said.

In closing, Dr. Carleton said, “If you’re looking for COVID-specific content, we also have that available up on the website for how to help people in the midst of COVID-19 challenges. Last but not least, there’s the link for our tool which is free (https://ax1.cipsrt-icrtsp.ca). It’s entirely anonymous. We paid extra to make sure we don’t crack anything except the number of times somebody opens up the tool on the website. So I encourage you to make use of that if you think that you would benefit from participating in those sorts of anonymous screening tools. There’s also a host of organizations across the country who provide similar kinds of data that provide trustworthy resources for mental health (see Suggested Resources, below). I encourage you to check that out if you have additional questions or would like more information.”

Self-Care Tips for Emergency and Disaster Response Workers

Adapted from the Center for Mental Health Services’ Disaster and Trauma at www.samhsa.gov

Normal Reactions to a Disaster Event

- No one who responds to a mass casualty event is untouched by it.

- Profound sadness, grief, and anger are normal reactions to an abnormal event.

- You may not want to leave the scene until the work is finished.

- You will likely try to override stress and fatigue with dedication and commitment.

- You may deny the need for rest and recovery time

Signs That You May Need Stress Management Assistance

- Difficulty communicating thoughts

- Difficulty remembering instructions

- Difficulty maintaining balance

- Uncharacteristically argumentative

- Difficulty making decisions

- Limited attention span

- Unnecessary risk-taking

- Tremors/headaches/nausea

- Tunnel vision/muffled hearing

- Colds or flu-like symptoms

- Disorientation or confusion

- Difficulty concentrating

- Loss of objectivity

- Easily frustrated

- Unable to engage in problem-solving

- Unable to relax when off duty

- Refusal to follow orders

- Refusal to leave the scene

- Increased use of drugs/alcohol

- Unusual clumsiness

Ways to Help Manage Your Stress

- Limit on-duty work hours to no more than 12 hours per day.

- Make work rotations from high stress to lower stress functions.

- Make work rotations from the scene to routine assignments, as practicable.

- Use counseling assistance programs available through your agency.

- Drink plenty of water and eat healthy snacks like fresh fruit and whole-grain breads and other energy foods at the scene.

- Take frequent, brief breaks from the scene as practicable.

- Talk about your emotions to process what you have seen and done.

- Stay in touch with your family and friends.

- Participate in memorials, rituals, and use of symbols as a way to express feelings.

- Pair up with a responder so that you may monitor one another’s stress.

Suggested Resources

Dr. Carleton referred to a host of organizations across the country that provide similar kinds of data to his own group’s website that provide trustworthy resources for mental health. Below is a smattering of places where he’s referred people in the past.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America – www.adaa.org

- American Psychological Association – www.apa.org

- Canadian Association of Cognitive and Behavioural Therapies – www.cacbt.ca

- Canadian Mental Health Association – www.cmha.ca

- Canadian Psychological Association – www.cpa.ca

- National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder – www.ptsd.va.gov

- Psychology Matters – www.psychmatters.ca

- Society for Traumatic Stress Studies – www.istss.org

Watch the Webinar

Visit goCANA.org/webinars to view a free, on-demand version of the complete webinar.

Q&A

After the main presentations were completed, time was reserved to take questions from those in attendance. Here is a summary of that interaction.

What benefits come from joining an association and being an active contributor?

Scott Smith spoke of how a helpful network formed locally through a collaboration of friends in Texas. They shared different resources as they were needed, such as additional body bags, manpower, and supplies. Especially in the beginning of the pandemic, formal and informal distribution networks—even among competitors—made vital PPE available locally. Local and national associations also provided critical updates to information about the rapidly changing circumstances as the pandemic unfolded.

Long hours can damage people if sustained for too long. Have you used early retired staff as a resource? Have you prepared them and brought them back into the workplace?

Scott found that the fast spread of the pandemic meant that some businesses couldn’t prepare in advance to increase staff. “There is no silver bullet to make this easy. We’ve all struggled with long hours, subbing with team members so we can get rest. Being organized and trying to prepare is the best way to get through this and prevent burnout,” he said. Scott wasn’t able to take advantage of bringing anyone back from retirement, but advised that if you know of people who are available to work part time and can rotate in, it would be a big help.

Would you like to comment on your experience of the use of Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) and its possible value in our field?

Dr. Carleton explained that Trauma Risk Management is one of many programs currently made available to try and help people with regular exposure to potentially psychologically traumatic events. One of the challenges about this method, and others like it, is that data about what ways, when, and how it is effective is relatively limited. Peer-led interventions can be helpful, but it’s not clear if one specific program is any better than any other. Reaching out for positive peer support—not just collective venting which can increase negative emotions—can be helpful, which TRiM supports.

How can we support each other in our own grief?

Dr. Carleton said that grief is a unique thing and shared the work of Dr. Katherine Shear on Complicated Grief. Grief is not something that’s clearly defined—you don’t have clear phases or end-point. Grief can last an entire lifetime, ebbing and flowing throughout, and in many cases it does. Grief in and of itself isn’t a problem, it’s not something to cure since it’s part of the human experience. If grief is leading to difficulties with destructive behaviors or debilitating, interfering with your job, then maybe seek help to better manage the symptoms of grief from an evidence-based professional. But grief is part of the human experience. While it’s not a pleasant emotion, it does also remind us to value all of the things we have right now because of the things we’ve lost before.

How can managers and colleagues spot signs of burnout and encourage people to seek help?

According to Dr. Carleton, the more open you keep communications, that peer connection, can help. But if you identify big behavior changes—someone normally jovial now lashes out, as an example—it’s a good indication that you should check in with them. The more engaged you are with your team with regular communication, the better positioned you are to support them.