By Leader Contributor Alan D. Wolfelt, Ph.D.

You don’t need me to tell you that COVID-19 has forced hundreds of thousands of American families to postpone services for a loved one who died during the pandemic.

While some have gathered in person for limited, socially distanced funerals and others have held online ceremonies of some kind, many have understandably decided it’s simply too difficult or unsafe to hold a ceremony right now. And lacking a better alternative, they have made vague promises to themselves and their family and friends that they will gather once the pandemic is over.

But even before the pandemic, families choosing direct cremation were apt to do the same — not always decisively choosing no funeral but instead allowing themselves the possibility of a future ceremony while making no concrete plans to have one.

Unfortunately, you and I both know that most of these postponed ceremonies will never take place. By my estimate, at least 80% will not. Life goes on, new crises and demands arise, and the idea of having a delayed memorial service fades further and further into the rearview mirror.

In my experience, here’s the problem with that: When no ceremony is held, mourning is never properly initiated. It can create a terrible, never-ending limbo for these families, especially the primary mourners. I call it “un-embarked grief” because these mourners often don’t leave the trailhead and venture into the normal and necessary wilderness of their grief. They have a much harder time fully acknowledging the reality of the death, which is the linchpin need of mourning. They also don’t receive the crucial public affirmation and social support a funeral provides.

Fortunately, these families have you in their corner. You are their funeral specialist. They don’t understand what they risk by not holding a funeral, but you do. They need you to be their advocate and guide. Not only can you help ensure that they hold whatever rites they can now, even if limited, you can also be the catalyst for making all those postponed ceremonies happen. I do appreciate that you’ve been busier and more stressed in the past year than ever before, so please think of this initiative as a team effort. More on that in a minute.

Planning Now for Later

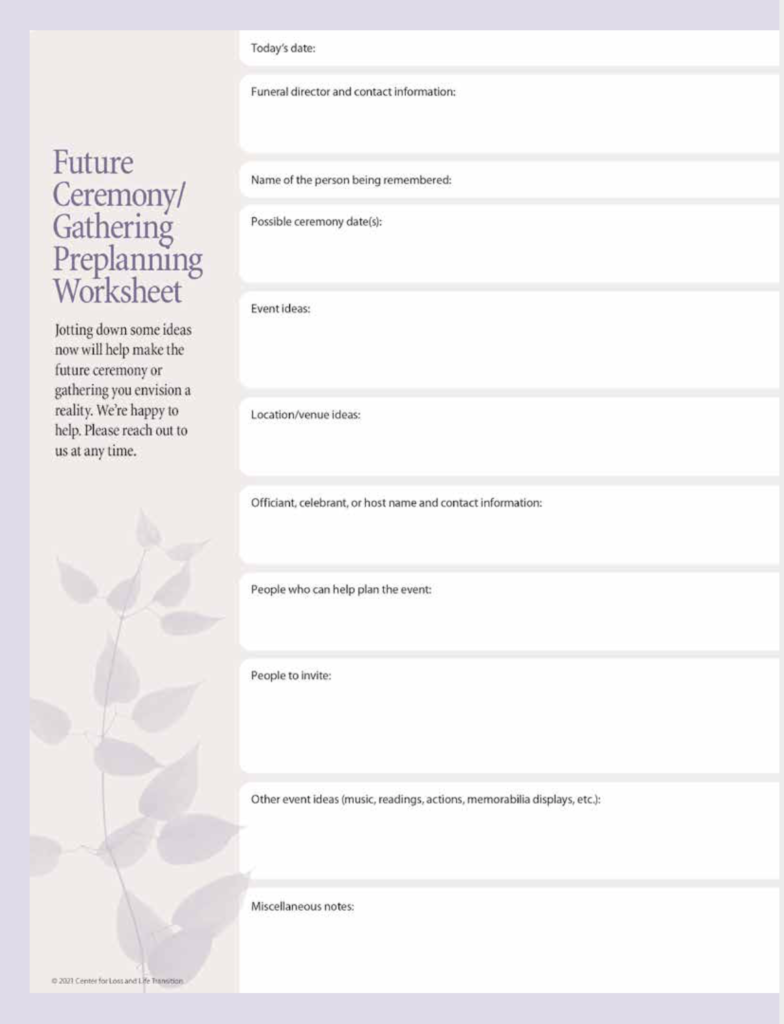

I propose that when the time is right — during an arrangement call or follow-up call or visit — you take it upon yourself to help these families put future plans on paper. I’ve created a simple pre-planning worksheet to help you understand what I mean. (See the image below.) Please contact me through my email noted at the end of this article if you’d like me to send you a PDF. You’re welcome to use it as is or adapt it for your funeral home’s use.

The goal is to capture the family’s early, vague ideas and help them develop those as much as possible now, while the iron is still hot. Writing down the plans makes them more concrete.

For example, I know a family whose patriarch recently died. The man had numerous friends and acquaintances, and he also loved ice cream. The family held a family-only funeral in their Catholic church — an excellent start and already more than many families are doing — and announced in the obituary that they’d be inviting the community to an ice cream social later this year.

Will they actually have the social? I don’t know. I sure hope so. But I do know that the conceiving of the idea itself makes it more likely, as does promising that specific future event in the obituary. Now the family has an image of a certain type of gathering in their minds, and their community members do, too. Talk of it is bound to continue, and that alone creates the momentum the idea will need to blossom into reality.

But if their funeral director had taken time to help this family think through and plan the future gathering in a bit more detail, the odds of it happening would increase even more.

Here are some things you can do now with at-need families that are postponing ceremonies.

You can initiate a conversation about what kind of ceremony and gathering they’d like to have in the future. Some are considering holding a full, traditional memorial ceremony in a church or at your funeral home. Others have less formal ideas in mind, like the ice cream social or a cars-and-coffee event for a car buff, or a garden gathering. The possibilities are endless.

You can suggest that they include mention of this specific event in the obituary. That way, their friends and family members will help hold them accountable.

You can help them think about a venue for their event and note some specifics on the planning form, such as contact names and phone numbers. Offering your facilities, when possible and appropriate, is also a good idea.

If the family is not already affiliated with a church or place of worship, help connect them with a celebrant in their community — maybe even a celebrant you have on staff. Whether it’s a religious officiant, a lay celebrant or a family host, you can jot down this person’s name, phone number and email address, and if it seems appropriate, you can even ask if it’s okay for you to pass along their contact information to the celebrant so he or she can reach out to the family in the days to come. And then — this is key — you can share or pass along follow-up responsibility to the celebrant, who may not be as overloaded as you are right now. The celebrant can then become the leader of the delayed-ceremony team.

From what you’ve learned about the person who died as you helped gather obituary details, you can suggest other elements that might help the family round out the future event, such as appropriate music, readings, memorabilia displays and more. Record that on the form, too.

You can help them brainstorm close friends and family members who could help with parts of the ceremony, such as the eulogy, readings, a tribute video or refreshments. You can help the family understand that the more people who feel invited to be part of the future experience, the better. In fact, inviting those helpers now, even if the ceremony is months away, makes the planning start to gel and helps everyone feel committed to and part of this important event. Add a few notes about this and also write down the family’s ideas about who to invite.

And finally, you can ask the family about a future date that might work for the memorial service. Having a prospective date on the calendar and in everyone’s minds makes the nebulous real. The family may not be able to pinpoint an exact date, but they can probably envision a month and maybe even which part of that month. Sometimes, a special date might pop up in the conversation, such as a birthday or anniversary, that might make a suitable ceremony date.

Send the family home with the form you’ve filled out, or if you’ve had a virtual arrangement, email the completed form. Even better, email it to a number of family members. Keep a copy for yourself and consider emailing them a duplicate PDF in a few weeks in case the form has been misplaced in the stress of the early days following the death.

In a short conversation of maybe 15 minutes, you have the power to move a family at risk of having no ceremony (and thus a forever stalled grief experience) from “not likely” to “probably.” And if your funeral home enlists administrative and community outreach staff and uses a care-contact calendar or process to follow up at regular intervals with these families, helping them firm up ceremony plans and troubleshoot hurdles, the odds will skyrocket. You get the ball rolling and others can help keep it going.

I’m a big believer in the philosophy of “do good things and good things will follow.” Even if your funeral home won’t be compensated for helping plan these future ceremonies, it’s the right thing to do. What’s more, focusing on families’ best interests promotes long-term goodwill. The families you help in this way will never forget you. You will be their hero, and they will tell others in the community about your above-and-beyond service and compassion.

And when you are a guest at that ice cream social, enjoying a banana split, and you take a moment to look around at all the smiles, tears and hugs surrounding you, you’ll feel affirmed that there is no greater purpose and privilege for your vocation.

Dr. Alan Wolfelt is recognized as one of North America’s leading death educators and grief counselors. His books on grief for caregivers and grieving people have sold more than a million copies worldwide and are translated into many languages. He is founder and director of the Center for Loss and Life Transition and a longtime consultant to funeral service. Email Wolfelt if you’d like to receive a PDF of the preplanning worksheet. 970-217-7069; drwolfelt@centerforloss.com; centerforloss.com.